Turin, 1931. A few feet from where Antonio Carpano was said to have invented vermouth nearly 150 years prior, the Taverna del Santopalato — that’s the “Tavern of the Holy Palate” — opened with a braggadocious bang. If we’re to believe the contemporaneous report from Italian daily La Stampa, March 8, 1931 would remain “impressed in the history of the art of cooking, just as the dates of the discovery of America, the storming of the Bastille, the Congress of Vienna or the Treaty of Versailles are indelibly fixed in the history of the world.”

The tavern’s dining room was sheathed in Italian aluminum like a bomb set to detonate the past, its patrons chewing their way toward the abolishment of the Ancien Régime.

The ingredients

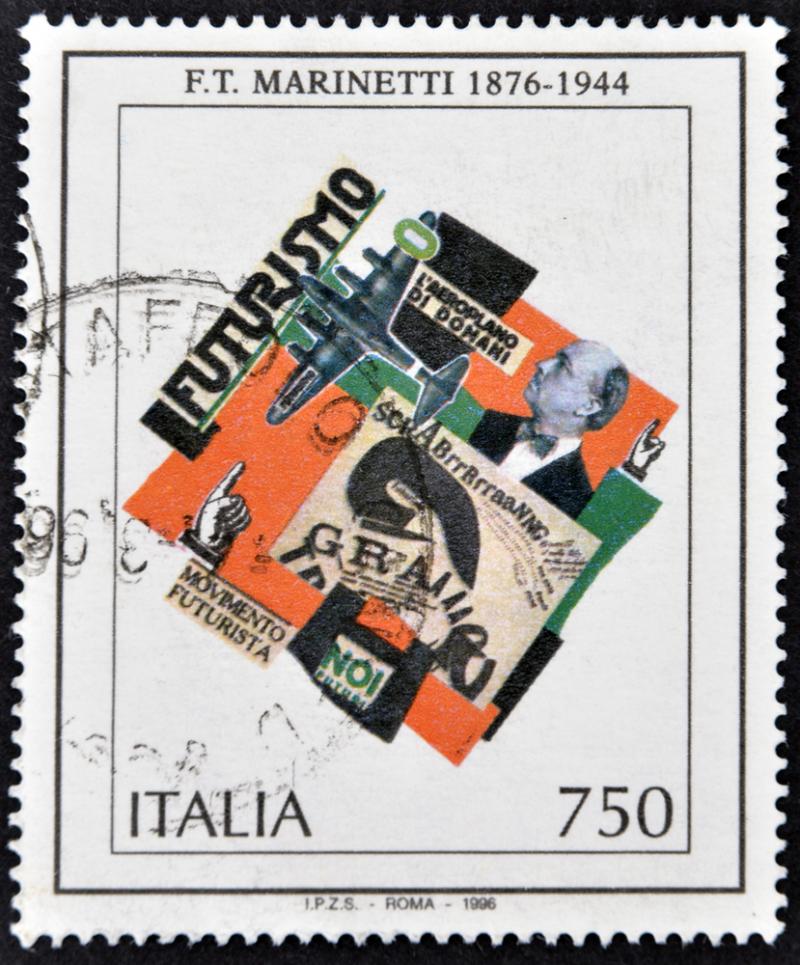

The multi-sensory menu at the Santopalato, made up of fourteen dishes, was inspired by poet F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto. Published on February 5, 1909 in the Bologna-based newspaper Gazzetta dell’Emilia, and two weeks later as a front-page story in the French daily Le Figaro, the supercharged text professed that “poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.” In line with his Fascist contemporaries and not unlike today’s American alt-right, Marinetti included the fairer sex among such “unknown forces”: The Manifesto expresses, alongside an embrace of war and xenophobia, an explicit “contempt for women.” Its ideas later spawned Marinetti’s 1932 work La Cucina Futurista (The Futurist Cookbook), which set out a food-as-fuel ethic for strapping, soldier-like adherents.

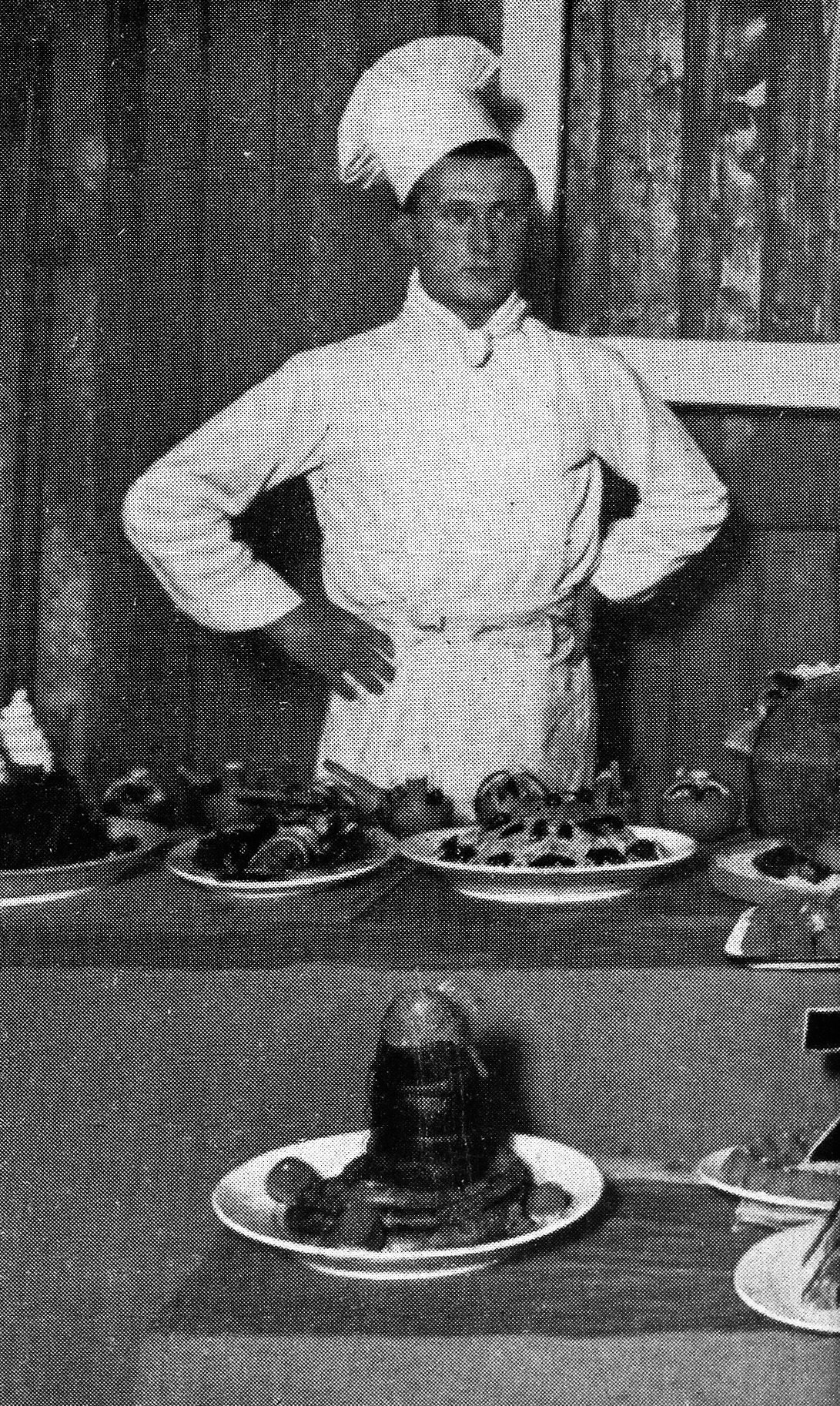

Aimed at enhancing virility — and thus casting “flabby” pasta as an enemy — the Santopalato's Futurist dinners would blend hyper-local (read: hyper-nationalistic) ingredients with an onslaught of absurd sights, sounds, tastes, smells and textures. Their synesthetic “Aerofoods,” in fact, found the diner nibbling on, say, a candied fruit with one hand while stroking textiles with the other; the “Chickenfiat” threatened to take on the flavor of the steel ball bearings with which it was stuffed.

As technological advances from the train to the plane to the Moka pot transformed Italy, the Futurists embraced a similar transformation of man himself. Marinetti and his ilk anticipated that machines would provide us with an “obedient proletariat,” freeing the would-be worker to spend his or her time striving toward perfection, not only in the kitchen, but on the battlefield.

The Futurists’ cuisine might sound impossible and unappealing today, but in their ideal hypothetical 2023, the Italian male would have long since completed his metamorphosis from flawed, sensitive individual to efficient, nationalistic cyborg, to whom a chicken flavored with ball bearings might sound quite delicious.

The execution

Sixty years after the Futurist Manifesto, in 1969, an unwitting but compelling companion piece to Marinetti’s own vision came along, courtesy of film director Marco Ferreri. Ferreri’s darkly satirical Dillinger è morto (Dillinger is Dead) would become the signature expression of the director’s long-running obsession with the end — not of the world, as many have suggested, but of modern man.

The film opens as the somber Glauco (Michel Piccoli), a designer of gas masks, is goaded into admiring one of his own creations. Locked away in a chamber, an unidentified subject gives Glauco an emphatic “a-OK,” confirming that his gas mask works as a defense against the poison of their own making. Glauco’s colleague celebrates their “success” by pontificating, complete with references to the German political theorist Herbert Marcuse, cluing in the viewer that this chamber is an allegory for the self-imposed crisis of isolation in industrial society. While donning a mask — not without theatricality — Glauco mumbles about his desire to quit, as the colleague's recitation continues. Predictably, neither of these “One Dimensional” men, as Marcuse would have described them, is capable of listening or being heard.

Returning from work to his own gas chamber — an amenity-rich, nouveau-riche apartment — Glauco mills about the space. Over the course of the evening, he embraces his beautiful, bed-ridden, pill-popping wife (era “It Girl” Anita Pallenberg), and half-heartedly ogles their ineffective, teeny-bopping French maid, Sabina (Annie Giradot, in her third collaboration with Ferreri).

Unsatisfied by the meal his wife has made for him and unable to connect with the maid, Glauco dips into the pantry as if into another dimension. (It’s in this moment that the set shifts from the real-life Roman apartment of postmodernist painter Mario Schifano to the home kitchen of Ferreri’s frequent collaborator, Ugo Tognazzi.) In the latter location, Glauco discovers a rusted pistol wrapped in old American and Italian newspapers reporting the arrest of the Great Depression-era gangster John Herbert Dillinger. The arms expert restores the crown of that anti-hero, disassembling the gun in a salad bowl, then dressing it in oil.

Glauco takes his meal alone at the dinner table, a Futurist poster not-so-subtly at his back. Distracted by the TV, he flips the channel from an old newsreel on the past glories of Italian bicycling — once the pride of the Futurists — to a documentary on Schifano, to a series of old home movies he projects onto the wall, inserting himself. Each is a progressively more “meta” advance in self-absorption.

The film’s “upshot,” if you will, finds Glauco miming his own suicide with the pistol he’s adorned red with white polka dots, and then — spoiler alert — murdering his wife in her sleep. Light and playful! Like the cavalier colors on the gun itself, Ferreri presents this homicide with shocking levity, liberating his character from his own domestic hell to the sun-kissed seas of Portovenere, which Lord Byron used as a font of inspiration.

Traveling back in time past Byron’s Romantic Age to that of the ancients, Glauco takes the place of a dead man on a ship moored in the cove, assuming the role of the mythical Greek sea-god, Glaukos, for which he is named. Crowned with an ancient diadem by the ship’s too-young, too-beautiful captain, Glauco sails off into a surreal, blood-red sun, his fate ambiguous.

The digestion

Symbol-dense and disturbingly disjointed, Dillinger is Dead responded cynically to a new generation of revolutionaries. While other filmmakers were portraying angry, fashionable youths intent on changing the world — which Ferreri would ape shortly after Dillinger’s release, in the overtly apocalyptic and dire Seed of Man — he here opts for a middle-aged, bourgeois weapons manufacturer.

So profoundly stripped of his own humanity that he confuses such basic conditions such as love and hunger with violence and death, Glauco’s radical act is a success, propelling him onward to new horizons. Yet given the rotten cause — we are what we eat, after all — the effect is equally flawed: His revolution complete, Glauco sails blindly into that ominous sunset, at best ensuring an end to modern man and his violent ways.

On its surface, Dillinger is Dead confirmed the fears of Pope Paul VI, who publicly denounced Freud and Marcuse at the time (the film contains many references to the latter). The pontiff blamed both thinkers for what he called the era’s “unbridled” eroticism and “animal, barbarous and subhuman degradations.”

But Ferreri considered his film a response to the degradation of “values, morals, economic relationships” which, by his estimation, “no longer [served] a purpose” in that era of social unrest. Yet after steadily addressing the consequences of alienation in modern society, through a misogynist protagonist incapable of recognizing his own obsolescence, Dillinger is Dead incriminates the past as a path to such degradation, a response to the chauvinist shortcomings of Futurism itself.

Here, Dillinger’s painted pistol isn’t just some surrogate phallus: As Marinetti prophesied, it is art, it is nutrition, it is man itself. With a steady diet of steel and speed, man’s homicidal impulse would no longer be a defect, but a feature.

Where to…

Eat

Once housing the Santopalato (Tavern of the Holy Palate), Via Vanchiglia, 2 in Turin now specializes in Turkish cuisine, presumably causing Marinetti to spin like a kebab in his grave. Those interested in ironically immersing themselves in Futurist history have some options, however. Having restored a dining room of Futurist frescoes, Verona’s Olivo 1939 offers specialities from The Futurist Cookbook upon request. Milan’s Lacerba — named for a Florentine pro-war newspaper that folded days before Italy entered World War I — flaunts the movement’s slick aesthetics, without its pesky disdain for pasta (and, hopefully, women).

Explore

One can see the kitchen in which “Dillinger’s gun” is discovered with a visit to the estate and winery of the late Ugo Tognazzi, in the Roman suburb of Velletri. Alternatively, visit the sea caves of Portovenere to trace the footsteps of Glauco and his predecessor, Lord Byron.

Stateside, Futurism and “man as machine” are prominent threads in the forthcoming exhibition From Depero to Rotella: Italian Commercial Posters Between Advertising and Art at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York, which opens February 16 and runs through June 10, 2023.

Read

Penguin Modern Classics has published a widely available paperback edition of Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook. Meanwhile, The Futurist Manifesto can be read in its entirety via controversial-text-cataloguer Books on Trial.

Watch

Though it took three decades for it to arrive stateside, Dillinger is Dead is available to American viewers through the Criterion Collection. Italian residents have more options, including RaiPlay.