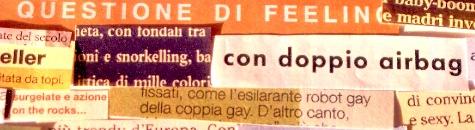

If you’ve flicked through an Italian newspaper or magazine, you’ll have spotted them. Italian walls daubed with graffiti? Italian teenage slang? No. I’m talking, of course, about English words.

For decades, Italians have been borrowing thousands of English words and formally making them part of the Italian language – words like ‘sexy’, ‘weekend’, ‘stress’, ‘shopping’, and ‘manager’.

Practicality lies behind the choosing of words with no Italian equivalent – ‘picnic’ is more concise than ‘merenda all’aria aperta’. But simple love of novelty prompts the snatching of many others – ‘freezer’ somehow livens up chats about the ‘congelatore’.

English loanwords are most noticeable in Italian journalism, advertising, business and science. Ultima-tely, they are a result of the economic might of the United States and the pervasiveness of its culture. English is thought attractive because it’s linked to prosperous people. It’s an ages-old assumption: to be like the rich you must talk like them.

As in a game of Chinese whispers, strange things often happen when one language borrows from another. Look at the English adoption of ‘al fresco’. In Italy, this phrase never refers to outdoor dining, and can even mean ‘in prison’!

Likewise, would you guess that an Italian ‘spot’ is a television commercial? Or that ‘footing’ means jogging, a ‘speaker TV’ is a newsreader, and a ‘golf’ is a cardigan?

Borrowing from other languages is a creative activity. Not only have Italians appropriated English meanings, spellings and pronunciation to suit their own purposes, they’ve allocated gender to English nouns (‘il budget’, ‘lo slogan’, ‘la gang’) and extended English words to make other Italian words (‘flirtare’ from ‘flirt’, ‘snobismi’ from ‘snob’, etc.).

Not Just a Modern Phenomenon

Italy has been having a colourful relationship with English and its speakers for 300 years. In the late 1700s, so-called ‘Anglomania’ swept Western Europe, partly because everyone was tired of admiring the French (who were annoyingly good at everything thought important in the 18th century) but also because British scientific and technological innovations were spreading English words for new things.

Italy has been having a colourful relationship with English and its speakers for 300 years. In the late 1700s, so-called ‘Anglomania’ swept Western Europe, partly because everyone was tired of admiring the French (who were annoyingly good at everything thought important in the 18th century) but also because British scientific and technological innovations were spreading English words for new things.

Italian interest in all other cultures and languages dried up in the 1800s, however, as the myriad states and kingdoms of Europe’s boot-shaped peninsula struggled to achieve a single national identity. (A unified Italy finally came into being in 1861). To bond together all the new Italians, everything had to be as Italian as possible.

As the 20th century got underway and the reins of the world seemed to be handed to America, Italians went crazy for the United States. Millions emigrated, seeking prosperity in the ‘land of opportunity’.

Back home, English was idealized as the language of American wealth and plenty, and many of its words were embraced into Italian – even when immigrants’ tales of hardship in the new world began to be heard.

And then the Fascists arrived. For 20 years, they encouraged Italy to be as economically, culturally, and politically independent as possible.

Naturally, racial and linguistic ‘purity’ were very highly prized. Italian dialects and minority languages were suppressed, and action was taken to ‘cleanse’ Italian of foreign words – including any used in the names of towns, hotels, and even surnames.

The Accademia d’Italia published lists of ‘illegal’ foreignisms and proposed Italian substitutes. The alien word ‘sport’, for example, should be replaced with ‘diporto’ or ‘ludo’ or ‘agone’ or ‘gioco’. ‘Bar’ must yield to ‘barro’, ‘mescita’, ‘quisibeve’, ‘bibitario’, or ‘bevitario’.

Violation of these guidelines could mean a hefty fine or even a six-month prison sentence, but the vast majority of suggested alternatives failed to catch on. A renewed craze for American culture, and for the English language, came with the end of World War Two. It would only intensify as the 20th century progressed.

And the Future?

Current research suggests the Italians are becoming less fascinated by America and more intrigued by the burgeoning European Union and all it might offer them. It’s unlikely that their attention will shift to other European languages, however, because English’s status is so entrenched and the language deemed so useful.

Current research suggests the Italians are becoming less fascinated by America and more intrigued by the burgeoning European Union and all it might offer them. It’s unlikely that their attention will shift to other European languages, however, because English’s status is so entrenched and the language deemed so useful.

English is the world’s lingua franca – currently known by about 2 billion people, or one third of the world’s population. Because no other language can put you in touch with so many people, English is overwhelmingly the most popular foreign language learnt by Italians (and all other continental Europeans). As more Italians acquire fluency, it’s likely they’ll smuggle fewer English words into Italian and keep the two languages separate.

Demand for English has become so great that certain secondary schools have made French compulsory for some pupils in order to avoid a mass unemployment of French teachers!

Many Italians view English as vital for career advancement.

While E.U. policies (and every individual’s rightful instinct to use and preserve their native language) ensure that English will, thankfully, never be the only language spoken in Europe, many linguists predict that the whole continent may eventually be bilingual - with every European having his or her native language for local use plus English for international communication.