Many travelers to Italy count silk ties and scarves among their favorite souvenirs, and silk accessories form a kaleidoscope of color in shop windows. The beautiful lakeside city of Como has been a leader in silk-making for more than a century, supplying the fashion houses of Milan and the rest of the world with high-quality silk. However, most of Como’s silk enterprises are open to the trade only. If you want to experience the authentic heritage of Italian silk-making first-hand, head to Florence.

[Stunning botanical garden decorated with mediterranean oleander flowers in Lake Como]

[Stunning botanical garden decorated with mediterranean oleander flowers in Lake Como]

Medieval Origins

The piles of silk ties and scarves that fill the shop windows of Florence are vestiges of a thriving historical trade in silk, wool, and other textiles. Florence was already established as a textile town as early as the eleventh century, and by the 1300s, trade in cloth was a major part of the Florentine economy. Its merchants made a mint by doing business throughout the rest of Europe. This long history of textile trading formed the basis for the city’s preeminence in the world of modern fashion.

Although silk had been imported to Florence throughout the Middle Ages and traded far and wide by Florentine merchants, it began to be dyed and finished in the city itself by the fifteenth century. A fiscal census of 1404 lists some one hundred silk weavers in the city at that time, and silk grew in importance over the course of the 1400s. Prior to this time, goldsmiths had been involved in the making of gold and silver thread to be used in textiles, but by the 1420s the silk makers were taking this on themselves. The silk guild, or the Arte della Seta, incorporated both silk merchants as well as producers, and silk emerged as an important part of the artisanal fabric of Florence.

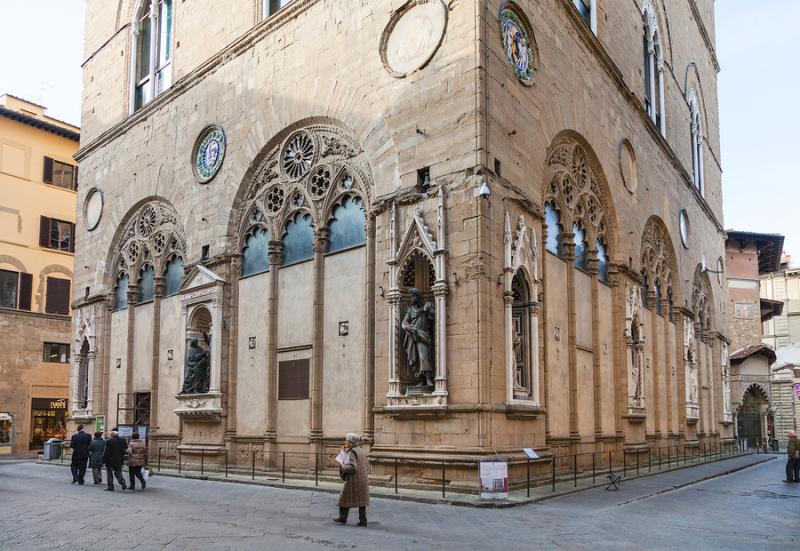

Bronze statue of St. John the Evangelist, on the Orsanmichele church exterior, who represents the silk guild

From the beginning, silk and other textiles were closely related to the leather trade, as they were all used to produce apparel. In addition, the same sheep hide might supply a maker of leather armor as well as a weaver. The complex Florentine guild system, or the arti, tightly regulated makers of everything from shoes, belts, purses, embroidery, hosiery, satin, taffeta, brocade, damask, velvet, and jewelry. Guild statutes controlled the production of these items and strict sumptuary laws stipulated the wearing of apparel made with them.

You don’t have to travel all the way to Italy to find authentic Italian silk. Just head over to the Italy Magazine shop.

How Silk is Made

Silk-making traces its roots to prehistoric China. The Silk Road—a well-trodden system of ancient trade routes—eventually brought silk to Westerners hungry for these exotic luxuries. By the Middle Ages, Florentine merchants found themselves well positioned to take advantage of this international demand for silk.

Ancient silk weaves at Antico Setificio in Florence

Ancient silk weaves at Antico Setificio in Florence

Incongruously, this deluxe fabric begins with a worm, or more accurately, a caterpillar. The process starts with the careful cultivation of silkworms, species Bombyx mori, along with the mulberry bushes and trees that serve as their habitat and diet. Sericulturists spread the sillkworms and fresh mulberry leaves on large trays stacked in special houses. There the silkworms feast on the leaves and produce a protein filament tightly wound into cocoons. Once completed, the cocoons are sorted and momentarily steamed, which kills the chrysalis, then boiled, which helps loosen the cocoon's delicate filaments. Then, the filaments are "thrown," a process in which several strands are twisted together to yield a thicker, stronger thread. The threads can then be dyed, making them ready to be woven or used in embroidery.

Like this article? Don't miss "The Hidden Florence Most Visitors Never See."

silk weaving at work: photo by Flickr creative commons celeste ramsay

silk weaving at work: photo by Flickr creative commons celeste ramsay

Initially, the Florentines imported the silkworm eggs, cocoons, and mulberry leaves from the East, using their well-connected international trade networks. As the silk industry grew toward the end of the fourteenth century, however, mulberry trees began to be cultivated across Tuscany, so the raw materials for silk making could be sourced in their own backyards. Some of the initial steps of the silk-making process—tending and reeling the cocoons, and spinning thread—were undertaken in silk workers’ homes. Weavers operated large wooden handlooms to produce bolts of silk and the dyeing took place in a process similar to that of wool. A central office organized the workers and commercialized the products. In Florence itself, silk production was destined both for apparel and accessories, as well as for textiles used in the home.

How to Buy Silk in Florence

Florence is a world fashion capital and it’s impossible to ignore the sparkling flagship stores of some of Italy’s most famous luxury brands. Closely associated with Florence, silk neckties and scarves are the bread and butter of many of these world-renowned designers. In addition, smaller Florentine boutiques do a brisk trade in silk accessories. Silk ties and scarves are durable, portable, and, if you know what you’re looking at, can be a good value for a high-quality Florentine souvenir.

Keep in mind, however, that the majority of silk ties and scarves in Florence are produced behind the scenes—perhaps in Florence or Tuscany, or in a factory far distant from the slick boutiques where they are sold. Therefore, it pays to be an educated consumer when it comes to shopping for these sought-after souvenirs, as you will not likely come face-to-face with the person who made them.

A number of synthetic fabrics can masquerade as silk, including acetate, nylon, and polyester. A scarf or tie may be composed entirely of synthetics, or may be made with a silk-synthetic blend. Be sure to examine scarves and ties carefully before buying.

Here’s what to look for:

- Sheen: Genuine silk is famous for its beautiful shine. As you turn the scarf or tie over in your hand in raking light, you should be able to see different colors shine through, the result of differently colored threads used in the warp and weft.

- Texture: Pure silk feels exceptionally smooth and slippery in your hands. When you rub the material vigorously between your hands, do you feel it begin to heat up? If so, it’s a good sign of authentic silk.

- Weave: Most scarves and ties are machine-woven, which makes genuine silk difficult to distinguish from synthetics, because the stitching of both appear perfect to the eye. Hand-woven silk, more common in upholstery and home textiles, incorporates small imperfections, or slubs, in the weave.

- Stitching: Check the stitching on the back of the tie or along the sides of the scarf. Artisanal ties will be more thickly woven, hand-folded, and hand-stitched. A high-quality scarf will have edges that have been rolled and stitched by hand in a thread that blends with the colors along the edges of the design.

- Pattern: On silk, a design may be woven or printed. Many textiles for the home, such as decorative pillowcases and upholstery, are woven, sometimes on a traditional handloom. In this case, you will see the pattern on both sides, with the underside distinguished by its slightly fuzzy appearance. In contrast, most scarves are printed using a silkscreen process using modern printing machines. The highest-quality scarves will be printed using a traditional, time-consuming process that involves pulling a different-colored screen across a metal frame by hand, building the design one color at a time.

- Sound: If you rub pure silk between your fingers, it makes a distinctive crunching sound that is often described as similar to walking on freshly fallen snow.

- Price: If the price is too good to be true, it isn’t real silk. Genuine silk is relatively expensive compared to synthetic imitations, often several times more.

If you’re still not sure, you can perform the “ring test.” Unless it’s exceptionally large or thickly woven, you can remove your wedding band or other ring and pull a silk scarf right through it. The scarf should glide through smoothly with no resistance. Synthetic fabrics tend to bunch or tug, making it difficult to pass them through a ring.

The definitive test of genuine silk, though, is the “burn test.” If you set the fringe or a thread of a silk scarf ablaze with a match or a lighter, you will hear it singe, then see it disintegrate into a tiny smoldering pile of fine ash, releasing an aroma akin to burnt hair. The burn test quickly unmasks plastic-smelling synthetic threads that curl or melt when burned. A silk merchant might be willing to perform this test for you, but I don’t recommend doing it in a store yourself!

Scarfing Up an Authentic Souvenir

Sadly, foreign-made knockoffs populate many of the boutiques selling scarves across Florence. The traditional Florentine scarf is a square, with edges that have been rolled and stitched by hand. Most merchants will allow you to open and spread out a scarf to check the pattern, weave, and stitching, as well as the quality of the silk, so take the time to examine it carefully.

High-quality silk ties and scarves can be had at many small boutiques across the city although you will not necessarily see them being made. The secret to unlocking the history of Florentine silk is to explore the wonderful historical enterprises making silk fabrics, tapestry, drapery, pillow covers, bedding, and other textiles used in the home. Herein lies the opportunity to experience the centuries-old tradition of Florentine silk and wool firsthand. In fact, several Florentine textile enterprises boast pedigrees that reach back to the 1600s. Some even use generations-old handlooms to create breathtakingly beautiful fabrics whose quality is truly among the world’s finest. Best of all, you can watch it being made.

Inside the showroom of ancient Florentine silk-makers, Antico Setificio Fiorentino

Inside the showroom of ancient Florentine silk-makers, Antico Setificio Fiorentino

- Antica Tappezzeria Borsellini, Via Maggio, 56, 055/21205.

- Antico Setificio Fiorentino, Via Bartolini, 4, 50124 Florence, 055/213861

- Casa dei Tessuti, Via dei Pecori, 20r, 055/215961

- Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio, Via Benedetto Fortini, 143, 055/6801340

Finally, many travelers to Florence are also looking to go home with a leather souvenir. Read on for more tips on Florentine leather shopping.

Laura Morelli is an art historian and historical novelist with a passion for Italy. You can find her guidebook series, including Made in Florence and Made in Italy, as well as her Venice-inspired historical novel, The Gondola Maker, in the Italy Magazine shop.