It’s looking to be a cold and wet Valentine’s Day on this side of the tracks, and what better way to spend the evening than snuggled up for a classic romantic film produced by those great maestri d’amore, the Italians?

This February 14, untold numbers of partners worldwide might be tempted to reach for Vittorio De Sica’s innocuously titled Matrimonio all’italiana (Marriage Italian Style), a cornerstone of Italian comedy that celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. But just as Cupid’s arrow can sometimes fly in unexpected directions, film titles don’t always fully convey what awaits an audience. Before you dim the lights and pop the prosecco, be warned: This one could spoil the mood if you’re not careful.

Naples in flames

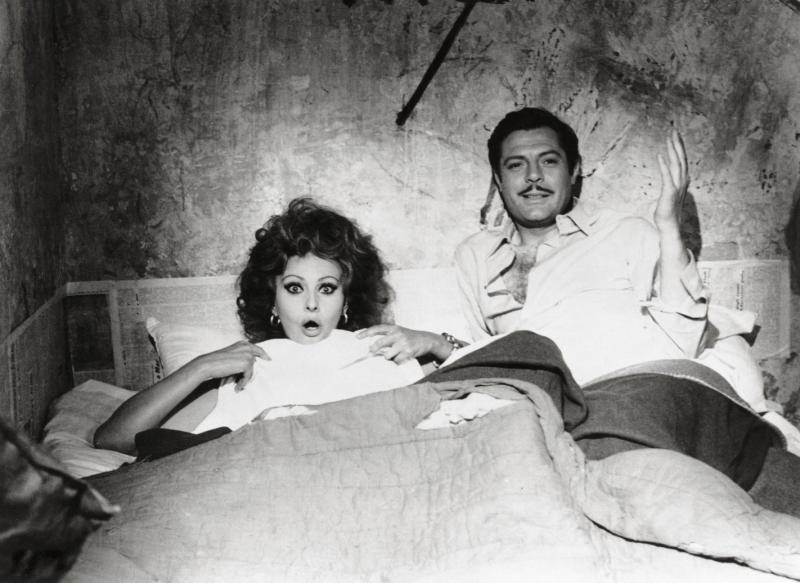

Adapted from Filumena Marturano, a play (1946) and subsequent film (1951) by the Neapolitan Eduardo De Filippo, 1964’s Marriage Italian Style tells the story of a complicated, two-decade romance between an eponymous prostitute (Sophia Loren) and a wealthy, gluttonous businessman named Domenico Soriano (Marcello Mastroianni).

Though De Filippo found success in the immediate aftermath of World War II by casting his sister, Titina De Filippo, in the titular role, mega-producer Carlo Ponti instead tapped his real-life wife Loren (who, like the De Filippo siblings themselves, grew up an impoverished, “illegitimate” child on the streets of Naples). Changing the title to capitalize on the success of Pietro Germi’s Divorce Italian Style (1961), Ponti paired Loren with Mastroianni after the duo’s Academy Award-winning turn in De Sica’s Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. In the process, he cemented their status as the definitive Italian couple, at least in the eyes of foreign audiences.

The resulting film — flush with symbolic color, flashy star power and a flashback-laden narrative that spans decades — is a far cry from De Sica’s early-career successes which helped establish the style of Neorealism. But rather than being any kind of saccharine paean to love, Marriage bears the wounds of war, class struggle, and the influence of both on gender politics at a time when the Italian economy began to boom.

The “romance” between Marturano (Loren) and Soriano (Mastroianni) is forged in the fire of war, with the pair first meeting against the backdrop of an Allied raid. Marturano, a teenage prostitute, hides in the bordello, preferring dying alone and anonymously to being saved and exposed to a judgmental public. Soriano, a wealthy, middle-aged owner of a local pastry shop who just happens to be patronizing the brothel at the time, seems either incapable or uninterested in playing the seminal hero who whisks the maiden to safety — but he’s unable to abandon her entirely.

Slicking his hair back, Soriano enters Marturano’s room, offering the audience one of the more unsettling meet-cutes in cinematic history (though it will later be topped by a cringeworthy first kiss which sees Marturano and Soriano embrace in a bombed-out shanty, oblivious to the crossed-out wartime homage to Mussolini looming behind their backs).

Such obliviousness is a defining feature of Mastroianni’s bumbling Soriano: Whereas the archetypal southern male, raised under the Fascist ideal, must be at once virile and protective of female virtue in the public sphere, Soriano unequivocally fails at these tasks (and without the slightest inkling of self-awareness). Mastroianni himself, on the other hand, was far from oblivious: Running counter to his reputation as the seminal latin lover, Mastroianni — who would have turned 100 this year — built a whole career out of playing this blundering Casanova. It’s a type the film scholar Jacqueline Reich calls the inetto, not only here, or in the case of Mastroianni’s famously impotent and hubristic protagonist in Mauro Bolognini’s Il bell’Antonio (1960), but in countless other occasions. But in Marriage, though the immaculately dressed Soriano seems to have emerged unscathed in a city devastated by war, Mastroianni’s sardonic send-up of the insensitive, morally bankrupt Lothario suggests that the era of Fascist chauvinism proved destructive even to those who embraced it the most.

Lonely in love

Marturano’s pursuits, meanwhile, whether in the name of illogical love or of middle class security, seem to come at the expense of the traditional family model. Born into desperate circumstances, forced by her father into a life of sex work, the adult Marturano constantly rejects a proletariat class that only wants to embrace her as their own. Occupying Soriano’s modern, middle-class pied-à-terre while managing his bakery — all the while subject to his condescension and emotional abuse — Marturano suffers the indignity of watching her three “illegitimate” children reared by a poor foster couple in the country. Yet when her impoverished but loving manservant Alfredo (Aldo Puglisi) offers to marry her and adopt her children without question, she only laughs in his face.

Desperation seems to corrupt Marturano and Soriano from the start. At first, Soriano lavishes Marturano with a taste of the good life in exchange for her youth and beauty, but he stops short of legitimizing her in public view. When Soriano seems determined to marry a younger, more urbane woman, Marturano responds by appealing to his sense of shame, feigning illness to dupe him into marriage at her own deathbed. Once it seems she has the upper hand, Marturano forgoes makeup or any attempt to subjugate herself physically for this cruel, incompetent man, and fully embraces what Reich calls the role of the “unruly” woman, gorging herself victoriously on the food in the fridge. Furious and feeling duped, Soriano threatens physical violence, but only hurts himself in the process: Somehow trapping himself under a piece of fallen furniture, he’s crushed by the collapse of his fragile machismo.

Later, as Marturano begins to assert her control over the home, like a matador taunting a bull, the emasculated Soriano responds in a way becoming of the modern man, flexing his muscle in the form of an attorney. Though defenseless in the court of law, the illiterate Marturano proves socially savvy once again: Mocking Soriano’s virility and pride, she informs him that one of her three children just might be his. Played once again, Soriano is driven mad by his own narcissism, and proves himself eager to provide for his heir — and only his heir — to ensure that his name might live on in honor.

Marriage Italian Style

As the film — this, your definitive Italian rom-com! — approaches its end, Soriano and Marturano meet on the slopes of Vesuvius as if on some prehistoric, class-neutral battleground. Marturano, unwilling to sacrifice three children for the sake of one, seems resigned to her own fate as Soriano finally lashes out like a gorilla. Tangled in the dirt and overcome by violence in the void of reason, the two finally embrace, giving into a love nearly canceled out by vanity and avarice.

Against all odds, with their three sons in tow, the couple is to be wed, and Soriano finally acknowledges all three children as his own. Feeling joy for the first time in her life, her family restored in a gesture of true love, Marturano weeps — and we all live happily ever after.