The hunt for Leonardo da Vinci's fabled lost fresco is to be filmed, Florentine culture officials announced on Monday.

''We have reached a five-year agreement with the National Geographic company to cover the search,'' said Paola Acidini, superintendent of Florence museums.

Acidini said the city was ''delighted that such a prestigious cultural media company has been attracted to this fascinating quest''.

National Geographic will pay the city council 50,000 euros a year over the five years to follow the probe inside Florence's Palazzo Vecchio.

It will turn the hunt into a documentary to be screened in 34 languages and 166 countries on its National Geographic Channel.

''I'm overjoyed that the search seems to have caught the world's imagination to this degree,'' said art sleuth Maurizio Seracini of the San Diego-based Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology (CISA3).

Seracini, the only real-life character in Dan Brown's bestselling thriller The Da Vinci Code, said National Geographic's involvement ''means there'll be no abatement of interest until we solve the riddle once and for all''. Seracini has been working on the case since he was a young researcher in 1975, when it was first suggested that Giorgio Vasari hid Leonardo's fresco of the Battle of Anghiari behind a wall rather than painting over it.

At that time, new imaging technologies provided tantalising clues but fell short of being able to let researchers 'see' clearly behind the current wall on which Vasari painted his own fresco.

The search was halted for lack of evidence in 1977 but has now been greenlighted again after multispectral imaging enabled Seracini to build up a stronger case.

Seracini has discovered that there is a thin layer of air behind the brick wall bearing the Vasari, raising hope that Vasari built a new wall to hide or protect the da Vinci masterpiece.

With the help of CISA3, Seracini's newly assembled team is employing new equipment to prove his theory. The first stage is to build a scale model of the wall in San Diego, using material from Palazzo Vecchio, and recreate bits of the original fresco behind it.

A barrage of equipment will be trained on the scale model. If they work, they'll be used back in Florence.

The tests will take place at the University of San Diego, a major funder of the one-million-euro project along with three private foundations.

In order to put the fresco fragments together, experts will pore over well-known smaller copies as well as documents detailing Leonardo's painting technique.

They'll also compare the imagined work to existing Leonardo frescos like The Last Supper.

Once the experts have a good idea where to look, they'll return to Florence to find what - if anything - is there.

The first results are expected at the end of this year, Seracini said.

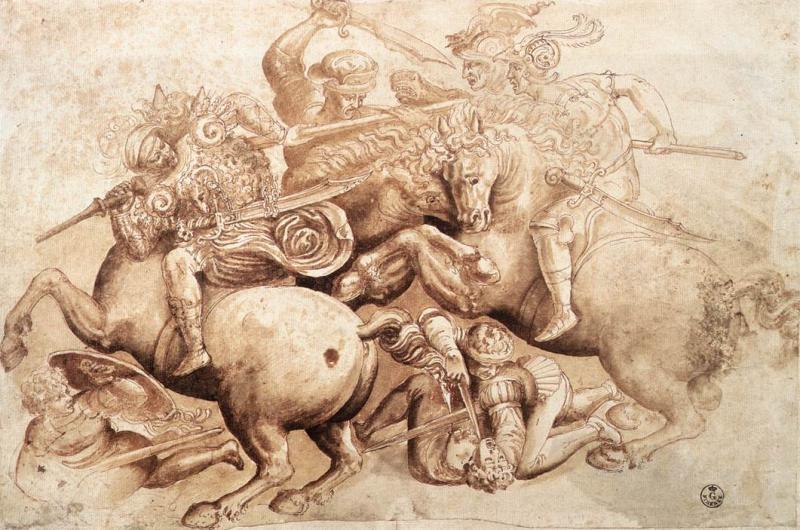

'ANGHIARI' KNOWN FROM COPIES, SKETCHES.

Florence commissioned The Battle of Anghiari to celebrate its famous victory over Milan on June 29, 1440.

It was described by sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) as a ''ground-breaking masterpiece'' that any artist simply had to see and study.

In a 1549 letter to a Venetian friend, Florentine painter Anton Francesco Doni called it ''a miraculous thing''.

The work has long been known from sketches and copies.

But the original was thought lost for ever - a victim of Leonardo's typically unorthodox decision to jettison the traditional technique of applying paint to wet plaster.

Leonardo (1452-1519) needed time for his painstaking approach and so used oils directly on the dry plaster in Palazzo Vecchio, the symbol of Florentine civic pride.

Like the Last Supper in Milan it soon began to crumble, helped on its way by a thunderstorm that hit the unfinished building.

Leonardo gave up and headed for Milan.

Originally, the Leonardo work was to have stood opposite another grand martial fresco by Michelangelo, on the other side of the Salone.

But Michelangelo didn't even start it.

Experts have been sure, however, that some version of Anghiari survived. Under pressure from Seracini, officials knocked through two square metres of the Vasari in 1979 - but found nothing.