As an art historian whose major research and writing has focused on women patrons of art and architecture in 16th century Italy, we wondered what brought Katherine A. McIver, professor of art history at UAB, to write a book that tells the story of cooking, eating, the experience of dining and the orchestration of a meal in Renaissance Italy. Below, she tells us how her latest book Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table came about.

I have had a long time fascination with and love of all things Italian and as I pursued my research, I often wondered what went on during everyday life, what was it like to live during this period? I kept trying to visualize what the rooms they inhabited looked like and what people actually did within them. So my first efforts to answer these questions was to look at the domestic interior – considered women’s domain and to look at material culture, that is, not the high priced altar pieces and sculptures that we normally associate with art patronage, but rather everyday objects including tapestries, credenze, cassoni (marriage chests), and all those things that were collected and kept within the home. Equally important were items used for dinner service: collections of maiolica ware, painted with lavish scenes, goblets made of crystal, silverware, fine linen table cloths and napkins and even the copper pots and pans used in preparing the meal.

Along the way, as I was sitting in various state archives throughout Italy sifting through a variety of documents from the period, including personal letters, household inventories taken after the death of an individual, account books that recorded expenses for running a household, and so on, I kept finding descriptions of kitchens and related spaces, of banquets and various meals, as well as references to food, recipes, gift giving and the like. Archival research can sometimes be tedious and a bit dirty! I’d order a “busta” (envelope) and be presented with a stack of dusty old papers and would pick through them and hope for the best – I could spend the whole day and find nothing at all or be lucky enough to find a long sought after inventory or will. Then I would spend hours or days reading and transcribing it, mulling over how it fit into my patronage project or noting, happily, when it outlined a kitchen or describe the space and its equipment.

Kitchen Writings

I came across inventories, letters, account books that let me into the life of many important renaissance families. From Parma, Laura Pallavicina-Sanvitale’s inventory, for example, was a room by room survey that included her kitchen layout and everything that was in the space: pots, pans, gridirons, tables, a credenza, plates, food and wine; yet, it did not mention the hearth – a permanent fixture that could not be sold as part of the movable goods being inventoried – so it wasn’t a complete picture of the her kitchen. I found interesting letters, like those of the marchesa of Mantua, Isabella d’Este’s to her brother, Alfonso d’ Este, duke of Ferrara, where she wrote out recipes for a favorite dish or asked about a specific cheese and where she might find it. Many of the letters also discuss health issues related to various foods, obtaining a good cook, or giving foods as gifts, like the artichokes that were sent to Ottavio Farnese, duke of Parma by his sister-in-law, because she knew he loved them. Account books, like those of Francesco Datini, not only record expenses for everyday meals, furnishings for the table and kitchen, but also for special events like banquets – so we now have an idea of what an average meal costs and the staggering costs of entertaining.

Fruit of the past

Food in Italy, who wouldn’t be interested in reading about what people ate, what they thought about food and how it was prepared i thought?

I have a passion for Italian food (and culture) and have taken several courses to perfect my cooking skills and an understanding of the Italian diet (Toscana Saporita in Tuscany for example) – so this was a natural for me. Over the years, I just kept collecting this material for a “some day” project. Along with the original sixteenth century documents, I turned to explore contemporary recipe collections and gastronomic texts, such as those by Maestro Martino da Como (Libro de arte coquinaria, 1470s), Cristoforo da Messisbugo (Banchetti, composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale, 1549), Giovanni Battista Rossetti (Dello scalco, 1584) and Bartolomeo Scappi (L’arte et prudenza d’un maestro cuoco, 1570), to name only a few. These texts are not just cookbooks with recipes, but guides to staffing and running a kitchen, serving and preparing a meal, and commentaries about diet and health.

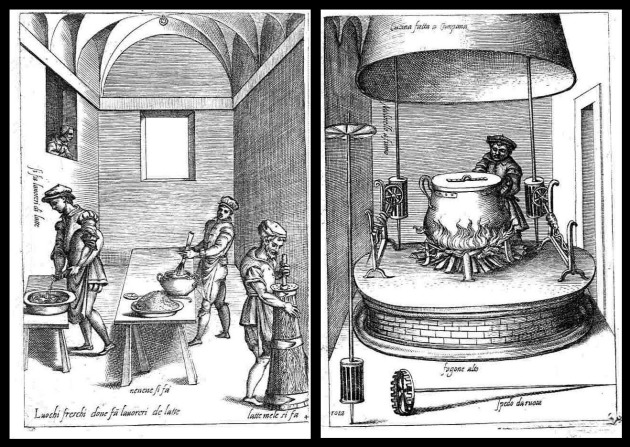

As an art historian, of course, I looked for related images: Scappi’s illustrations of various kitchens, preparation rooms, and cooking equipment were among the most informative, though an ideal; paintings like Veronese’s Marriage at Cana show us just how elaborate table settings for banquets could be, give us a sense of how the meal was served and what people ate (for more on this painting, see my essay, “Banqueting at the Lord’s Table in Sixteenth-Century Venice,” in Gastronomica, 2008). Scappi’s engravings and Veronese's paintings though present us with an ideal. So by combining images with contemporary writings I managed to get a fairly clear picture of the meal and how it all came together.

Sharing my findings

Of course, given my original research, I never lost sight of the women and while the Renaissance world of the cook, his staff and banqueting service remains the domain of men, women played a significant role in the book and not just as participants and ornament at major banquets, but as people who had something to say about the food they ate, the health of their husbands, sons and family, the banquets they attended and the cooks who prepared those meals.

Over several years, I kept thinking about the material, but I didn’t know how it would evolve: an article, a conference paper, perhaps a book, but later – as academic requirements for my position as a Renaissance art historian meant that writing such a book just might not help in terms of promotions, raises and other career advancements.

Obviously, I had to see what might have been written on the topic and if my material warranted a book, so I started with two of Ken Albala’s Eating Right in the Renaissance, 2002 and The Banquet: Dining in the Great Courts of Late Renaissance Europe, 2007.

So I built a solid background and came to realize I really had something significant here. The real turning point for the project came with the unearthing of a nearly complete set of documents, in the state archive in Rome, for the preparation of several meals in honor of Pope Sixtus V hosted by Duke Bernardino Savelli and his wife, Duchess Lucrezia Anguillara at Castel Gandolfo in 1589. I stumbled across these incredible documents while looking for Lucrezia’s inventory and household accounts, so purely by accident. The various lists, menus and other bits of paper tell us how the staff planned the menus with elaborate lists of items to be purchased, rented or borrowed, as well as hiring more kitchen staff and attendants. The preparations being made were not just for the pope, his entourage, and guests, but for everyone involved in the festivities, from the lowliest stable boy to the pope himself – about three hundred people in all. My next step was to email Ken Albala, professor of history at the University of the Pacific about the documents to see what he thought, and with his encouragement and enthusiasm, I presented my findings at the Renaissance Society of America conference held in Venice in April 2010; this paper became an essay in a collected volume of essays published by Ashgate in 2013 – so I was on my way! This also led to organizing other conference session on dining in Renaissance Italy.

So I built a solid background and came to realize I really had something significant here. The real turning point for the project came with the unearthing of a nearly complete set of documents, in the state archive in Rome, for the preparation of several meals in honor of Pope Sixtus V hosted by Duke Bernardino Savelli and his wife, Duchess Lucrezia Anguillara at Castel Gandolfo in 1589. I stumbled across these incredible documents while looking for Lucrezia’s inventory and household accounts, so purely by accident. The various lists, menus and other bits of paper tell us how the staff planned the menus with elaborate lists of items to be purchased, rented or borrowed, as well as hiring more kitchen staff and attendants. The preparations being made were not just for the pope, his entourage, and guests, but for everyone involved in the festivities, from the lowliest stable boy to the pope himself – about three hundred people in all. My next step was to email Ken Albala, professor of history at the University of the Pacific about the documents to see what he thought, and with his encouragement and enthusiasm, I presented my findings at the Renaissance Society of America conference held in Venice in April 2010; this paper became an essay in a collected volume of essays published by Ashgate in 2013 – so I was on my way! This also led to organizing other conference session on dining in Renaissance Italy.

My next big break came when I attended my first Roger Smith Cookbook conference in February 2012 in NYC and met Ken Albala with whom I had many intense discussions about my work. As general editor of the series Studies in Food and Gastronomy for Rowman and Littlefield, Ken asked that I write a proposal for a book, this was followed by a contract – and the rest is, as they say, history.

------

Katherine McIver is professor of art history at UAB and an expert in Renaissance and Baroque art, architecture, and material culture.

You can find her book Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table in our shop.