As part of our ongoing series on ancient Roman life, to commemorate 2000 years since the death of Rome's first emperor August, celebrated in 2014, Carol Kings heads to the Circus Maximus to report on one of the most exciting sports events of the time: chariot racing.

You can read part one of the series, "The Romans: What They Ate" here; part two, "The Romans: Marriage and Weddings" here; part three, "The Romans: Top 5 Emperors" here; part four, "The Romans: What they Wore" here; part 5, "The Romans: Gladiators" here; part 6, "The Romans: Housing" here.

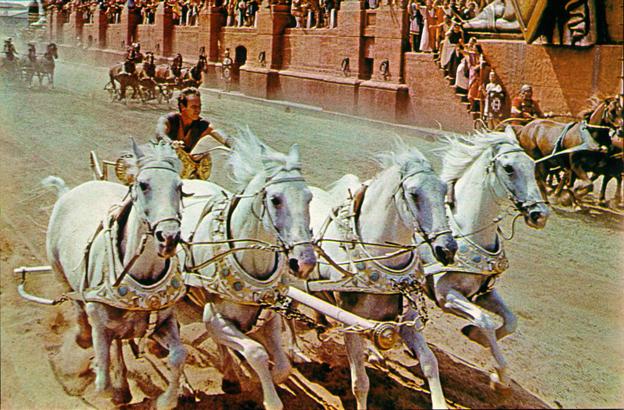

The nine-minute chariot race featured in the 1959 movie ‘Ben Hur’ has become one of cinema’s most famous sequences. In Ancient Rome, chariot racing was the equivalent of today’s Formula One, but with galloping horses rather than cars. Cheering crowds were thrilled by the speed and skill of drivers, who were fêted by emperors and the public alike. Like F1 drivers, charioteers earned large sums and were regarded as the courageous heroic sportsmen of the day.

The Romans likely borrowed the custom of chariot racing from the Etruscans, who were in turn influenced by the chariot races of the Greeks. Chariot races were held at the Panhellenic festivals in Greece and in Roman times, and at the ludi sacred games staged during religious festivals.

In republican and imperial times, Roman chariot races, or circenses, were staged in arenas known as circuses. The centre of chariot racing in Rome was the Circus Maximus, which could seat 250,000 people. A circus was divided down the centre by a low wall, the spina. Races were for four-horse chariots, quadrigae, and two-horse chariots, bigae. Chariots started the race speeding out of spring-loaded gates known as carceres. Four to six chariots competed in a heat by driving up one side of a circus track and down the other, rounding the metae (conical pillars) at each end. A heat consisted of seven rounds of the circus.

[Photo: the site of the Circus Maximus in Rome today]

The race host, the magistrate, signalled its start by dropping a cloth called a mappa. Once a race had started, charioteers would jostle to move in front of one another and cause their opponents to collide into the spina wall. Competitors were ruthless in their desire to win and did not hesitate to cause a crash that could lead to a rival’s chariot being destroyed.

The chariots were made from wood and leather, making them light to handle, and aiding speed and manoeuvrability. They were low and rounded at the front, open at the back, and mounted on small wheels. Typically, a biga was drawn by two horses yoked to a pole and a quadriga by four horses yoked to two poles. The Romans recorded information on horses’ names, breeds and pedigrees, and – like charioteers –horses had their own fan following. Popular racehorses even received awards from emperors.

Charioteers were usually slaves, however, on the racetrack, they were professional sportsmen. They wore leather helmets and short tunics with padding around the torso and thighs. Charioteers stood upright in chariots, wrapped the horse reins around their waists – knotting them at the back – and leaned in the direction they wanted their chariot to turn; their hands were then free to use a whip. Chariot racing was a dangerous sport because in the event of a crash a charioteer could be dragged around the track, risking life and limb, unless he managed to escape by cutting the reins using a falx (curved knife) to release himself. However, the rewards for a successful charioteer could be great. Winners were crowned with laurel leaves and awarded prize money, but best of all, if they won enough races, charioteers could buy their freedom. Nevertheless, the life expectancy of even a celebrity charioteer was usually short given the deadly nature of a life spent on the track.

In republican times, chariot teams belonged to private owners. In imperial times, teams were owned by contractors who acted as owner-managers. The teams were distinguished by four colours: blue, white, red and green. Later, two other colours were added: purple and gold. Charioteers could switch teams, just as footballers are traded between teams today.

Each team had its own band of fans that followed it keenly. Watching the skill of the charioteers was not the only reason crowds flocked to the races – they placed bets on different colour teams, too. Passions among fans ran high. Sometimes disappointed fans rioted after watching their team lose. Pliny wrote about the extreme gesture of a grieving fan who threw himself on the funeral pyre of a charioteer from the red team. Chariot racing may have only been a game, but fans’ love of the sport appears to have been as strong as that of any enthusiastic group of football or motor-facing supporters in the 21st century.