The Renaissance was a bastion of male achievement; whether in the field of sculpture, painting, letters or statecraft, few women were able to break through society’s self-imposed barriers. One of the rare women to have the opportunity to demonstrate her artistic talents was the extraordinary Sofonisba Anguissola, born in the Lombard town of Cremona in 1532. Her enlightened father provided her with a solid and varied education which led her to take the unprecedented step of an apprenticeship in an artist’s studio.

In Rome, it wasn’t long before the young Sofonisba was being introduced to Michelangelo himself. The great man was impressed with her drawing and encouraged her to portray the even more technically advanced features of a crying child, which she did with great dexterity and skill.

In fact, one of Anguissola’s most famous portraits is of her own siblings, Lucia, Minerva and Europa playing chess. The two older sisters are involved in the game as the younger one looks on giggling at Europa’s hands raised in defeat. Two of the girls painted also went on to become artists, but with considerably less success and skill.

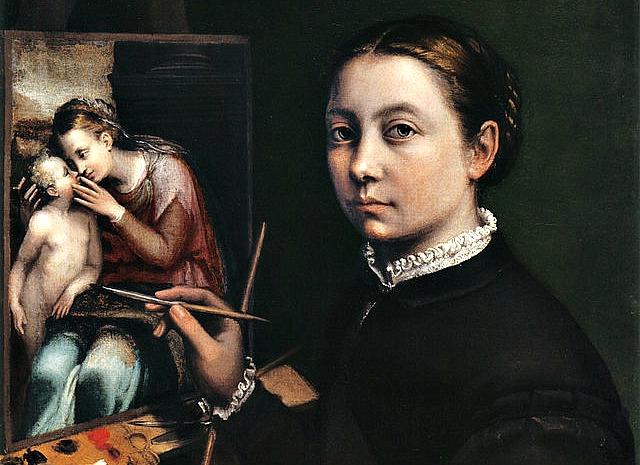

Sofonisba was apprenticed to the Cremonese master, Bernardino Campi. In the long tradition of painters appearing in their canvases, later epitomised by Diego Velázquez in Las Meninas, she painted herself on to the easel of her teacher, who, turning away from his supposed portrait of Sofonisba, stares out towards the viewer. This particular picture was composed in the 1550s, before her career really took off.

Her big break came shortly afterwards when she went to Milan and painted the Spanish Grandee, the Duke of Alba. Impressed by the results, he recommended her services to the Spanish Royal Court, specifically, Phillip II and his wife, Elizabeth of Valois. In order to avoid the breaking of courtly convention, she was not appointed as an artist, but a lady-in-waiting. However, that didn’t stop her pursuing her career, as evidenced by a portrait of the king now hanging in Madrid’s Prado Museum.

The stiff manners of the Spanish Court required a far more formal style of portraiture. These formal traditions also saw her married off to Fabrizio Moncada, the son of a Sicilian viceroy. There were compensations for an arranged marriage and Sofonisba could comfortably continue her painting with a generous pension from Philip II. It also meant that she could move back across the Mediterranean, as the couple settled in Palermo. Two years after Fabrizio died in 1579, she married for love; Orazio Lomellini a Genoese sea captain was to become her second husband.

Her later years were spent in the home of her beloved husband in Genoa and finally back in Palermo, where she could receive visitors and hand out advice based on her considerable years of experience.  One of her last visitors of note was Anthony van Dyck. His portrait of the aged Sofonisba can now be found in the van Dyck collection at Knole House in Sevenoaks, UK. Her drawn, elderly features and grey hair, covered in a white headscarf, still don’t detract from the agile turn of her mouth and the lively look in her eyes. Continuing to paint well into her eighties, her final efforts would be hindered by fading eyesight, thought to be the effect of cataracts.

One of her last visitors of note was Anthony van Dyck. His portrait of the aged Sofonisba can now be found in the van Dyck collection at Knole House in Sevenoaks, UK. Her drawn, elderly features and grey hair, covered in a white headscarf, still don’t detract from the agile turn of her mouth and the lively look in her eyes. Continuing to paint well into her eighties, her final efforts would be hindered by fading eyesight, thought to be the effect of cataracts.

Outlived by Orazio, she was buried in Palermo’s Church of San Giorgio dei Genovesi, just off Via Squarcialupo. Her tombstone can still be seen, complete with the inscription commissioned by her husband, commemorating his love for Sofonisba and her impact on the art world, an impact that undoubtedly opened up opportunities for others who would follow, including the unfortunate Artemisia Gentileschi, whose own life in the world of painters and patrons would need another few pages.