The cathedral complex in Florence kicked off a six-year restoration of the baptistery's dome mosaics earlier this month — the first time they've been restored in over a century. To mark the occasion, we’ve rounded up some other standout mosaic cycles around Italy.

Perfected as an art form by the Romans and Byzantines, mosaics have stood as both status symbols and spiritual guideposts. Stories are brought to life through the use of tesserae — cubes of stone, ceramic or glass — and every viewing experience leaves an impression. Here's where to find some of the most memorable mosaics around Italy, spanning floors and facades of churches to embellished nooks of private palaces.

Palatine Chapel, Palermo

Like so many of the mosaics in this roundup, the Palatine Chapel’s treasures in the Norman Palace of Palermo are a visual fusion of several different cultural influences. But given their location in Sicily, one of the world’s textbook “melting pots,” the impression of multicultural hands at work perhaps comes through more vividly. Byzantine, northern African, Arabic and European glories and styles merge in one monument: Think Fatimid arches paralleled with Arabic touches on the ceiling and glittering Byzantine mosaics throughout.

The oldest and, according to many, best technically executed mosaics are those in the dome and its drum, which date from the mid-12th century and show Christ as Pantocrator — “ruler of all” — flanked by angels. But the collective impression of the entire chapel, including the ornamental mosaics lining its transept, is what stays with you more than any single piece of the equation.

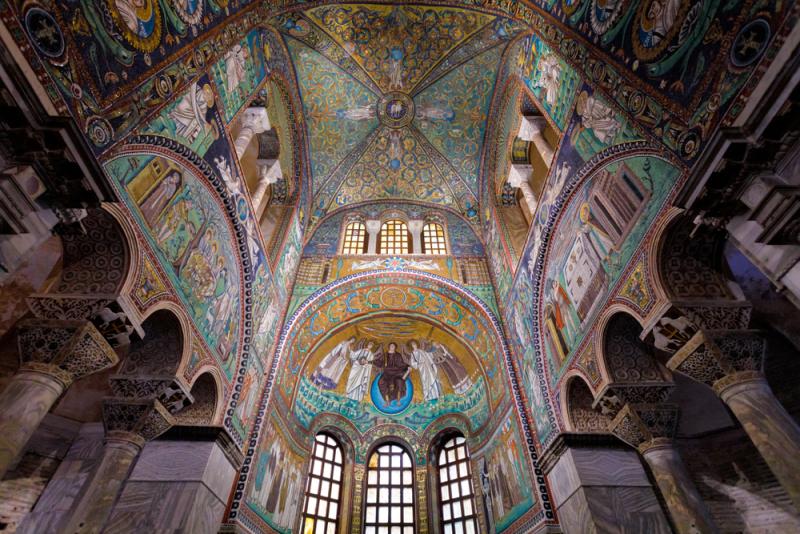

Various early Christian monuments, Ravenna

The Byzantines are credited with transforming Ravenna into Italy’s mosaic capital. Seat of the Roman empire in the 5th century and then of the Byzantines up until the 8th century, this city boasts some of the finest examples of early Christian mosaics and monuments in Italy.

Ravenna’s mosaics were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1996, and the most impressive in the lineup are spread across the Church of San Vitale, the Basilicas of Sant’Apollinare in Classe and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, and the Mausoleums of Teodorico and Galla Placidia. What makes them stand out apart from the general artistic prowess is the wonderful blend of Graeco-Roman tradition, Christian iconography, and oriental and Western styles.

Saint Mark’s Basilica, Venice

It’s true, in Venice you’ll have far more visitors to compete with for views of the mosaics than you will in Ravenna. But it’s hard to talk about the triumph of medieval mosaics as an art form without talking about la Serenissima, where the art of the time was influenced both by the nascent Gothic style (western) and by Byzantine art (eastern).

The dazzling golden mosaics in Saint Mark’s Basilica — the oldest of which date back to the 11th century — symbolize the “divine light.” Many of the Saint Mark’s mosaics have been restored after numerous fires over the centuries and today can be seen adorning the five doorways, portraying saints, apostles and Christ Pantocrator.

Basilica of Aquileia, province of Udine

Intrepid mosaic lovers will want to veer off the tourist trail and head to the Basilica of Aquileia in the province of Udine in Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Set on the edge of the Adriatic lagoons, Aquileia, a former Roman colony, was founded in the late 2nd century BCE.

The Romanesque-Gothic Basilica of Aquileia features a magnificent floor mosaic that is believed to be the largest early Christian mosaic in the western world (at 760 square meters). The enormous work dates back to the 4th century and is rich in allegory that uses plants, animals, skies and constellations as vehicles. The depiction of a fight between a rooster and a tortoise is perhaps the most famous image from the basilica’s mosaic cycle, and represents the broader struggle between good and evil, Christ and the underworld.

Cathedral of Orvieto

The Cathedral of Orvieto’s incredibly intricate façade is covered in polychrome mosaics, some of which date back to the 14th century and are attributed to designs laid out by Cesare Nebbia.

Conceived and created according to an impressively exacting scheme, the facade's embellishments show the most important episodes in the life of the Virgin Mary, to whom the cathedral is dedicated. The splendid tile motif also shows the baptism of Christ, then converges upwards to the scene of the crowning of the Madonna. The rose window that visually anchors the mosaics is attributed to Andrea di Cione di Arcangelo, better known as Orcagna.

Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome

In the heart of Rome’s always-trendy Trastevere quarter is where you’ll find this blockbuster basilica. The anchoring point of the expansive piazza of the same name, the church was most likely the first official Christian place of worship in ancient Rome. Outside, your eye is immediately drawn upward to the facade’s 12th-century mosaic, which depicts the Virgin Mary and Christ child between 10 elaborately dressed women bearing lamps. Inside, the shimmery pageantry continues, with many gilded mosaics depicting vivid visual tales of the Virgin Mary. Many of the tiles were laid in the 12th century during the reign of Pope Innocent II and just after his death.

Website down at publication time; more information via Turismo Roma

Santa Maria Annunziata, Otranto

This cathedral in Puglia holds within its walls a little-known yet monumental treasure. Along the church floor, some 600,000 tiles laid by a monk named Pantaleone form an immense polychrome mosaic (about 52 meters long). Commissioned around 1165 by Jonathas, Archbishop of Otranto, the cathedral mosaic is remarkable for the sheer volume of biblical scenes it depicts, and for the fact that it was completed in just under two years. The predominant image of the Otranto mosaic is the “tree of life;” its trunk extends down the entirety of the nave, designed to accompany the viewer on their spiritual journey.

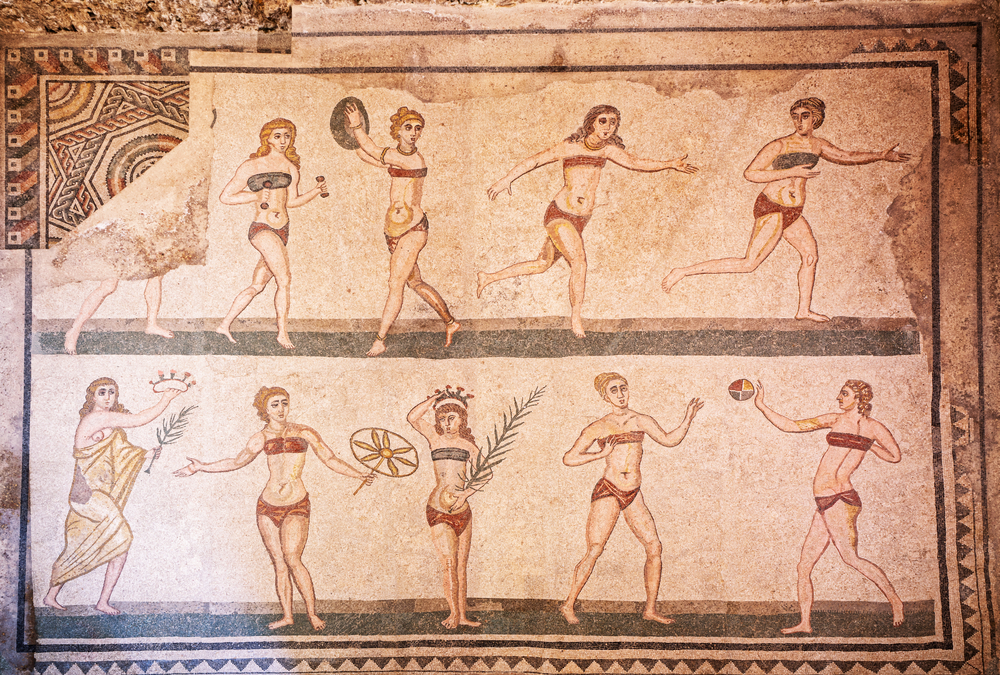

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1997, Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily’s Piazza Armerina — a town, not just a square — was built in the 4th century CE on the remains of a villa once belonging to Maximianus Herculeus, Diocletian’s co-emperor. Buried beneath the mud for thousands of years, the villa was only discovered in the late 19th century.

Admired for their outstanding colors and craftsmanship, the villa’s mosaics are believed to have been influenced by north African culture and perhaps executed by African artists. Within the Hall of the Palestrini (female gymnasts) is a series of well-preserved mosaics that are often referred to as the “Bikini Girls.” The women depicted are wearing what’s best described as the workout gear of the time, and are shown engaging in weight-lifting, discus throwing, running and ball games. Also notable is the “Great Hunt” on the floor of the antechamber, which shows hunters using dogs and capturing a variety of wild game.