After the Medicis were restored to power in 1512, Machiavelli was charged with conspiracy, imprisoned and tortured. On his release, he retired to his family estate at Sant’Andrea in Percussina to live out the rest of his life in exile. There Machiavelli began writing ‘The Prince’, which he dedicated to Lorenzo de’Medici. Some suggest that Machiavelli was a realist and wrote about political methods that were common at the time. Some believe that ‘The Prince’ is a satire and a veiled insult to the Medicis in support of a republican government. Some assert that Machiavelli intended the work to be a plea to the Medicis to use whatever means to create a state that could resist foreign invasion. Others think that ‘The Prince’ is a warning regarding the use of tyranny. The interpretations of ‘The Prince’ are many and British philosopher Lord Bertrand Russell even called it a “handbook for gangsters.”

After the Medicis were restored to power in 1512, Machiavelli was charged with conspiracy, imprisoned and tortured. On his release, he retired to his family estate at Sant’Andrea in Percussina to live out the rest of his life in exile. There Machiavelli began writing ‘The Prince’, which he dedicated to Lorenzo de’Medici. Some suggest that Machiavelli was a realist and wrote about political methods that were common at the time. Some believe that ‘The Prince’ is a satire and a veiled insult to the Medicis in support of a republican government. Some assert that Machiavelli intended the work to be a plea to the Medicis to use whatever means to create a state that could resist foreign invasion. Others think that ‘The Prince’ is a warning regarding the use of tyranny. The interpretations of ‘The Prince’ are many and British philosopher Lord Bertrand Russell even called it a “handbook for gangsters.”

A version of ‘The Prince’ was distributed via correspondence during Machiavelli’s life but the printed version was published in 1532, five years after he died. Since then, its philosophy has influenced rulers including Henry VIII, Benito Mussolini, Bettino Craxi and Silvio Berlusconi, as well as intellectuals, writers, historians, political scientists and philosophers. At one point, the treatise was regarded as so dangerous it was placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, it is said that ‘The Prince’ is the most widely translated book in the Italian language.

However ‘The Prince’ is viewed, it is a remarkable work in its examination of how the state should function and the need for strong centralised political power for a state to function effectively. Although written during the Renaissance, some Italians still see the relevance of its message for Italy today. In June 2013, young Italian businessman Jacopo Morelli spoke at a conference of the youth wing of the Italian employers’ federation Confindustria. He said: “In the summer of 1513, Machiavelli began writing ‘The Prince’, in an Italy plagued by uncertainties and struggles. Today, after 500 years, similarities are [still] there... that should serve as a wake-up call to government to do more to move Italy away from the fear and uncertainty the economy faces today.”

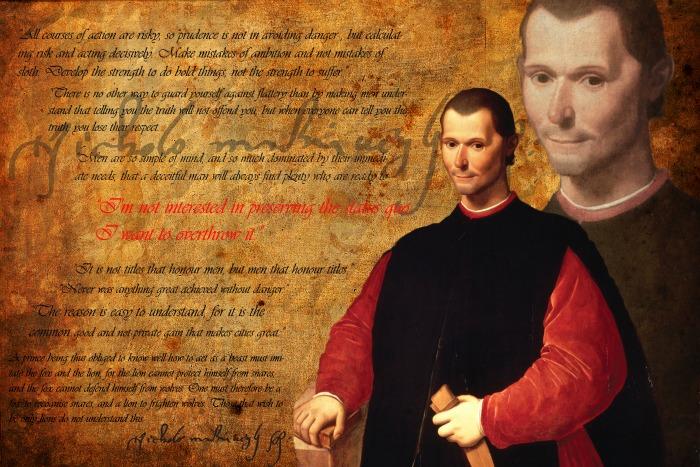

TOP 5 QUOTES FROM ‘THE PRINCE’

A version of ‘The Prince’ was distributed via correspondence during Machiavelli’s life but the printed version was published in 1532, five years after he died. Since then, its philosophy has influenced rulers including Henry VIII, Benito Mussolini, Bettino Craxi and Silvio Berlusconi, as well as intellectuals, writers, historians, political scientists and philosophers. At one point, the treatise was regarded as so dangerous it was placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, it is said that ‘The Prince’ is the most widely translated book in the Italian language.

However ‘The Prince’ is viewed, it is a remarkable work in its examination of how the state should function and the need for strong centralised political power for a state to function effectively. Although written during the Renaissance, some Italians still see the relevance of its message for Italy today. In June 2013, young Italian businessman Jacopo Morelli spoke at a conference of the youth wing of the Italian employers’ federation Confindustria. He said: “In the summer of 1513, Machiavelli began writing ‘The Prince’, in an Italy plagued by uncertainties and struggles. Today, after 500 years, similarities are [still] there... that should serve as a wake-up call to government to do more to move Italy away from the fear and uncertainty the economy faces today.”

TOP 5 QUOTES FROM ‘THE PRINCE’

“...it is necessary for a prince, if he wants to maintain his position, to develop the ability to be not good, and use or not use this ability as necessity dictates.”

From Chapter I ‘On the Things for which Men, and especially Princes, are Praised or Blamed’.

“...experience shows that nowadays those princes who have accomplished great things have had little respect for keeping their word and have known how to confuse men’s minds with cunning.”

From Chapter IV ‘Whether Princes Should Keep Their Word’.

“... a new prince , when he has the chance, should cunningly nurture some opposition, so that in overcoming it there is a subsequent increase in his standing.”

From Chapter VI ‘Whether Fortresses and Many Other Things Commonly Used by Princes are Useful or Useless’.

“The first impression one forms of a ruler’s intelligence is based on an examination of the men he keeps around him.”

From Chapter VIII ‘On the Secretaries Who Accompany the Prince’.

“A prince should...[choose] wise men in his state who alone are given the freedom to speak to him truthfully, and only about those things he asks and nothing else.”

From Chapter IX ‘How Flatterers are Avoided’.

“...it is necessary for a prince, if he wants to maintain his position, to develop the ability to be not good, and use or not use this ability as necessity dictates.”

From Chapter I ‘On the Things for which Men, and especially Princes, are Praised or Blamed’.

“...experience shows that nowadays those princes who have accomplished great things have had little respect for keeping their word and have known how to confuse men’s minds with cunning.”

From Chapter IV ‘Whether Princes Should Keep Their Word’.

“... a new prince , when he has the chance, should cunningly nurture some opposition, so that in overcoming it there is a subsequent increase in his standing.”

From Chapter VI ‘Whether Fortresses and Many Other Things Commonly Used by Princes are Useful or Useless’.

“The first impression one forms of a ruler’s intelligence is based on an examination of the men he keeps around him.”

From Chapter VIII ‘On the Secretaries Who Accompany the Prince’.

“A prince should...[choose] wise men in his state who alone are given the freedom to speak to him truthfully, and only about those things he asks and nothing else.”

From Chapter IX ‘How Flatterers are Avoided’.