What makes Italy special, even more than Florence’s art riches, Rome’s grandiose temples or Venice’s palazzo-lined canals, are its many villages, a myriad tiny little borghi, sheltered behind thick stone walls, guarded by tall crenellated towers, watched over by the sober façade of the local church.

Some of these villages, especially those in central Italy, have become destinations in their own right—San Gimignano, Monteriggioni and Greve in Chianti spring to mind. But there are many more, perhaps tucked away in the mountains, or up winding roads on a hilltop, which are worth discovering.

Because winter is coming, and there isn’t a better time to visit a mountain village than winter, when the lamplights cast a trembling glow over the snow, and the streets are imbued with the scent of chestnuts, mulled wine and burning logs, we have picked three of the best small borghi—one in the North, one in the Centre and one in the South of Italy—to explore in the cold season.

With a grand total of 3072 inhabitants among the three of them, you have probably never heard their names before—but trust us when we say they all deserve a place on your travel map.

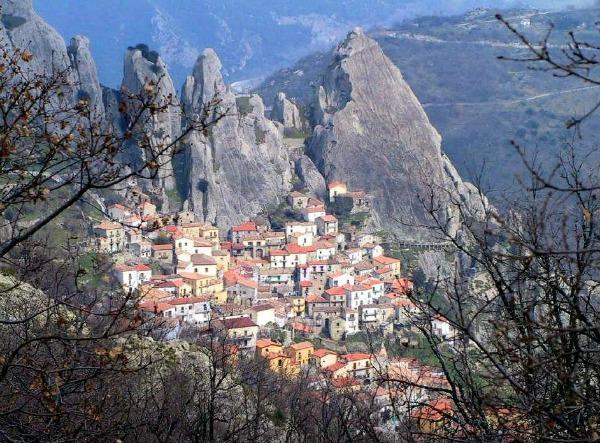

Castelmezzano, Basilicata

Towering peaks, curvy spires, bizarre sandstone crops of a dazzling candour surround the village of Castelmezzano, in Basilicata, in a rocky embrace. Castelmezzano, which translates into middle castle, takes its name from a Norman fortress that was once halfway between Pietrapertosa and Brindisi Montagna. The ruins of the fortress are still there, up at the top of a steep flight of stairs carved in the sandstone of a hill which humans have now left and which has been reappropriated by hawks and eagles. Below it, the village homes tumble down along the mountain slope—the rich palazzos of the local nobility, the secret network of sandstone-carved porticoes linking village streets and squares, the churches (one of which is carved in the rock) blending three centuries of statuary and architecture, from austere Middle Ages to ornate Baroque. And for the very brave, a steel cable linking Castelmezzano to Pietrapertosa allows visitors to glide like angels over the jagged Basilicata mountains (in summer only).

Towering peaks, curvy spires, bizarre sandstone crops of a dazzling candour surround the village of Castelmezzano, in Basilicata, in a rocky embrace. Castelmezzano, which translates into middle castle, takes its name from a Norman fortress that was once halfway between Pietrapertosa and Brindisi Montagna. The ruins of the fortress are still there, up at the top of a steep flight of stairs carved in the sandstone of a hill which humans have now left and which has been reappropriated by hawks and eagles. Below it, the village homes tumble down along the mountain slope—the rich palazzos of the local nobility, the secret network of sandstone-carved porticoes linking village streets and squares, the churches (one of which is carved in the rock) blending three centuries of statuary and architecture, from austere Middle Ages to ornate Baroque. And for the very brave, a steel cable linking Castelmezzano to Pietrapertosa allows visitors to glide like angels over the jagged Basilicata mountains (in summer only).

For more information see www.castelmezzano.net (in Italian only)

Pescocostanzo, Abruzzo

The peaks of the Alto Sangro valley rise in sinuous curves around Pescocostanzo, a small village in the heart of Abruzzo. The mountains here are forbidding and you’d think Pescocostanzo would have been cut off from the world until the modern era.

While the wild mountainscape did encourage a self-sufficient economy based on wool, however, between the Renaissance and the 18th century, the village was a key stop the Via degli Abruzzi, which linked Naples to Florence. Under the enlightened government of Vittoria Colonna and her successors, it flourished artistically as well as economically, acquiring architectural marvels that are rarely seen in a village of its size. A short walk along its pretty lanes takes in grandiose Baroque churches with monumental altarpieces, sober 16th century palazzos, and the elegant, joyous lines of Rococo buidings.

Pescocostanzo’s prosperity also attracted craftsmen from around Italy, who set up shop there and brought with them filigree jewellery, wrought iron working, lace-making and embroidery skills, which persist to this day (the village has a lovely little museum devoted to pillow lace).

Pescocostanzo also has an intricate, somewhat bizarre folk heritage. Several traditional Abruzzese fairy tales are set in the village, and many folk remedies and beliefs were developed over time. For example, should a witch get into your home intent on hurting your children, you only need burn a hole in her skirt to ward her off. Not that you are likely to ever meet one in Pescocostanzo, but still….

For more information see http://www.pesconline.it

Glorenza, Trentino Alto Adige

At the foot of the bare, church topped Colle di Tarces lie a handful of whitewashed houses, tightly wrapped in the embrace of thick fortified walls.

Glorenza, in the Val Venosta, in Trentino Alto Adige, is the size of a hamlet, but it is actually a town—possibly the smallest one in Italy.

It was already a town in the early 14th century, when it was referred as such in official correspondence by a local duke. It is in the Renaissance, however, that Glorenza truly comes into its own. Duke Ludovico il Moro of Milan and the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I met there in 1496, but, only three years later, the town was destroyed by Swiss troops. Story has it that Maximilian initially cried over the ruins—then decided to take a more proactive approach and had the whole place rebuilt behind huge, safe walls.

Today, large battlements broken up by more than 300 arrow slits and guarded by bulky towers stand guard over the carved doorways, elegant bow windows and frescoes facades of Renaissance palazzos. The odd masterpiece from later days lines the streets—the 17th century church dell’Ospedale, for example, or the graceful 18th century Castel Glorenza, built around an ancient medieval bastion.

But there is more to Glorenza than historic architecture. The town is famous for the local speck—a smoked cured ham—which is served with spelt or rye and buckwheat bread. It makes a perfect starter to follow with hearty Tirolese meal—think dumplings in broth, and beef and potatoes sauteed with onions—before ending in glory with a juicy, sweet, mouth-melting apfelstrudel made with the aromatic apples from the area.

For more information see http://www.altavenosta-vacanze.it/