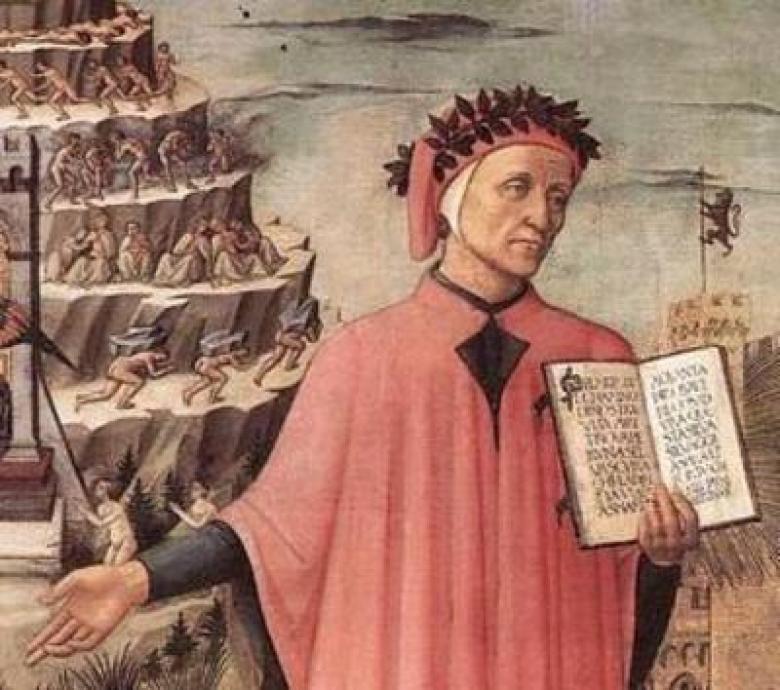

Dante—one short word, one mononym—because of the words written by one man, has come to mean so many things. Beauty. Complexity. Man’s quest in life. Redemption. The Afterlife.

Italians call him “The Supreme Poet”, or simply “The Poet”. During his lifetime and over the centuries, the reach and importance of Dante’s words grew and grew until it reached the heights Dante himself describe in his Paradiso (Paradise):

O somma luce che tanto ti levi

da’ concetti mortali…

(O highest light, lifted up so far

Above all mortal thinking…)

His epic Commedia (Comedy) became Divine.

But as a Catholic, and a religious one at that, Dante would likely have been the first to proclaim that he was just a man.

Early Life—The Making of Legend

When Dante was just nine years old, he first glimpsed Beatrice Portinari, but Dante was soon after betrothed to another noblewoman, Gemma di Manetto Donati, who bore him many children. Beatrice passed away in Dante’s youth, but she was his only love, his muse and his soul’s protection during his darkest moments.

In his teens, Dante became involved with a group of poets who would later be known as the founders of Dolce Stil Novo (Sweet New Style) poetry: Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Brunetto Latini, and Cino da Pistoia. Expanding on Guido Guinizzelli’s focus on a female love object to bring the spirit of the poet toward the divine, these poets transformed their muses into heavenly messengers and paved the way for Petrarch and his Laura.

Vita Nova (New Life), produced toward this end of this period, is Dante’s most significant work aside from the Commedia. Dante intersperses his early poetry with commentary and narratives showing his journey as a poet, philosopher and lover. First, he focuses on his suffering without his lady, then, he shifts the focus entirely to praising her, and finally, he realizes that his love is transcendent—the evolution of Cavalcanti’s earthly love, embodied metaphorically by his own Beatrice walking behind Cavalcanti’s Giovanna in Vita Nuova’s climax.

Dante’s Downfall: Political Passion

During his years in Florence, however, Dante’s passion was divided. His poetry, his studies, and his love for Beatrice on the one hand, and his family, political loyalty, and love of Florence on the other.

Dante’s family was loyal to the Guelphs, a political faction in Tuscany in the late 13th and early 14th centuries that supported the papacy against the Ghibellines, who supported the Holy Roman Emperor. He held political office in support of the Guelphs, fought in battles between the two factions, and served as an escort for Charles Martel of Anjou, who later quashed the Ghilbelline threat.

Family agendas in Florence subsequently divided the Guelphs into White Guelphs, favouring less papal interference in Florentine affairs, and Black Guelphs, who ultimately triumphed. Dante, unfortunately, was a White Guelph, and it was because of this internal feuding that he was banished from his beloved Florence for the rest of his life.

A Divine Legacy

Even in death, Dante’s personage remains relevant. His remains, currently entombed in Ravennna, where he died in exile, haunt the City of Florence, which has erected an empty tomb in the Basilica of Santa Croce in his honour, adorned with the words “onorate l’altissimo poeta (honour the most exalted poet)”. The remainder of the verse, from Dante’s Purgatorio (Purgatory)—l’ombra sua torna, ch’era dispartita (his spirit, which had left us, returns)—is notably absent.

Dante's Tomb in the Basilica of Santa Croce - Florence

But his spirit lives on in Florence every day. Plaques on the narrow streets and alleys of the medieval city centre, where Dante himself once walked, display verses from his poems to hundreds of millions of passing pedestrians each year. The church where he first saw Beatrice is preserved, a small space pierced by the daintiest rays of light from the small window, just as it was in the 13th-century. His face, with his characteristically sharp Etruscan nose, stares down from the side of the National Library, an alcove in the Uffizi arcade, and a pedestal in the Piazza Santa Croce.

Above, beyond—and certainly before—Shakespeare, Petrarch and Machiavelli, Dante united the lyricism of poetry and the philosophical ideals of the Classical period with the volgare (vernacular) to create enduring literary magic.

Whether or not it was his goal, through his words, his poetry, and his codification of the Italian language, Dante became immortal.